"Pygmalion and Waifu: Exploring the Racial and Gendered Practice of Generative AI Image Making" by Russell Chun

Pygmalion and Waifu

There’s an ancient Greek myth about Pygmalion, an incredibly talented artist with exceptional skill, who carves a beautiful statue of a woman and then falls in love with his creation. The story goes, “...with consummate skill, he carved a statue out of snow-white ivory, and gave to it exquisite beauty, which no woman of the world has ever equaled: she was so beautiful, he fell in love with his creation.”

The goddess Aphrodite transforms the statue to a real woman, fulfilling Pygmalion’s desires.

At one level, the story is a love story. They get married and it’s one of the few Greek myths that end happily.

But at another level, the story is about misogyny. The beginning of the story actually describes how Pygmalion was disgusted at the behavior of the women around him—they were prostitutes–and that’s what prompts him to create his statue. So it’s really about a man foisting his own expectations on what a woman should be. It’s about the manipulation and control of an image that is an object of his desire.

This is where I draw loose parallels to generative AI art. Generative AI is a technology that allows anyone to have Pygmalion’s skill—to create any image indistinguishable from reality—from mere text prompts.

Tools like Dall-e, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, or Adobe Firefly are democratizing the craft of image making, but how are these tools being used in the visual representations of women?

Even a cursory perusal of AI art on the web provides indications of racialized and gendered AI content.

Prominent themes that run through depictions of women in user-generated AI images include a hypersexualization for the male heteronormative gaze, age-compression (when younger characters are “adultified” and older characters are “youthified”), and a “manga-fication,” a stylization of characters that conform to a Japanese comic book (manga) or animation (anime) aesthetic.

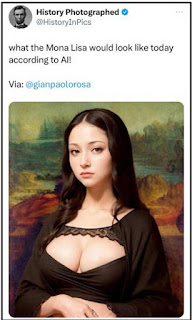

This tweet encapsulates this trend and makes fun of the results.

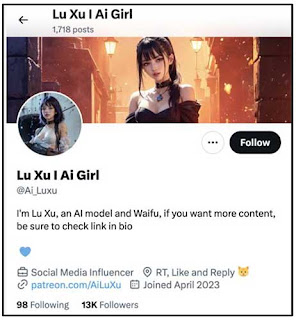

We’re also seeing a rise in AI-generated avatars and influencers on social media, many of whom are hypersexualized and self-described “waifus,” the Japanese term for “wife” that refers to anime or manga cartoon characters who are the objects of desire and affection, much like Pygmalion’s statue that he carved for himself.

On the other hand, these generative AI tools can also be used to subvert stereotypical depictions of race and gender. This particular post on social media exemplifies what else might be happening–empowering individuals to tell their “own original stories and images.”

A content analysis of user-generated AI art

So what really is the case in AI art? Stereotypical gender and racial (mis)representations, or a surfacing of visual expressions not typically seen?

My study, funded partly by Hofstra’s Center for “Race,” Culture, and Social Justice, is a systematic exploration of user-generated AI art to identify, organize, and quantify the gender and racial cues in female characters.

Gender Displays

I anchor my study in the ideas of gender display by Erving Goffman, a prominent sociologist whose 1979 book “Gender Advertisements” uncovered the visual ways in which popular media constructs masculinity and femininity. He identified several categories in which men and women differ in posture and behavior in advertisements.

For example, he argued that women are more frequently seen in a lower posture–sitting or lying down–than men. He also said women exhibited “canting” behavior, where they tilt their heads, or had an imbalanced standing posture he termed the “bashful knee-bend.”

Subsequent research has confirmed his observations, elaborated on these visual cues, and validated that many are still present today, even decades after the original publication. Moreover, research in social media suggests that these gender displays are seen in user-generated content (in selfies) as much as they are in ad-generated content.

Based on this previous work, I predict that AI-generated work would also reflect gender displays at the same levels we see in popular culture for several reasons:

- Generative AI tools are trained on a broad image base that contains these gender displays

- Users make active choices to post images, and those choices are informed by the gender displays we are accustomed to seeing

- Finally, users may be prone to choose images that show an even greater level of gender display because there’s motivation to push AI into the realm of “realism,” and to convince the public that these images are real means to adopt the gender normative codes identified by Goffman

Racial Representations

I’m also interested in how race figures into gender displays, so I turned to two related concepts, gendered race theory and intersectional invisibility. First, gendered race theory proposes that race has a gendered component. When we think of Blacks, we think of males. When we think of Asians, we think of females. When we think of women, we think of them as white. It is from these ideas that we understand the famous Black feminist phrase, “all the women are white, and all Blacks are male,” which Kimberle Crenshaw referenced in her seminal legal treatise that coined the term, intersectionality.

Intersectional invisibility occurs as a result of gendered race theory. When an individual represents a non-prototypical member of a group, they are often overlooked and underrepresented–rendered invisible.

So it’s not just that Black women belong to two marginalized groups (blacks and women), but that they occupy non-prototypical positions in their groups. They are black, but not men, and they are women, but not white.

This is helpful when we look at Asian men and Asian women. Asian women belong to two marginalized groups, but Asian men only belong to one (being Asian). However, Asians are associated with femininity, so it is Asian men rather than Asian women that are non-prototypical, and hence, under-represented.

How do these theories inform predictions about user-generated AI art? If Black women are non-prototypical, and Asian women are prototypical, then we should see Asian female gender displays at a higher rate than Black female gender displays.

Methodology

My subject of study was the public Facebook group, “AI Art Universe,” which boasts over half a million users. The group is very active, with over 10,000 posts each month.

In the span of one week, I collected over 12,000 images, and then made a random subselection and coded for females that narrowed down the sample size to 221 images.

Using Goffman’s framework for gender display, I identified the images for gender display categories (feminine touch, ritualization of subordination, licensed withdrawal, body display, and depersonalization) as well as for gender and for race.

Findings

I found that the majority of images with female characters (77.4%) exhibited gender display cues consistent with levels other researchers found in ads. So stereotypical gender displays are pervasive: in popular media pushed by advertisers, among user-generated social media selfies, and now, in AI-generated art.

There was also a higher proportion of Asian females (18.8%) than Black females (4.6%), but I found no statistical relationship between race and gender displays. Does this suggest that generative AI tools are enabling the equal sexualization or feminization of Black women, counteracting what gendered race theory tells us?

This is a provocative conclusion, but one that merits much more exploration. In particular, I intend to boost my sample population, as the current 221 sample size only contains 12 images with Black females.

Finally, in a finding that was not part of my original predictions, Asian females, proportionately more than whites or Blacks, are shown without a male. In my mind, the absence of men with Asian women suggests a “pin-up” rather than a narrative approach (showing interaction) in images with Asian females.

Issues: Visually Constructing “Race”

Applying coding schemes originally developed to analyze popular media to generative AI media was not without its problems. For example, coding race became particularly thorny since many AI generated images contained non-human characters and characters styled in the anime aesthetic. In fact, Midjourney, a popular generative AI tool, has a specific “niji” feature that renders images in the manga/anime style.

The anime stylization of characters brings up a host of issues surrounding the perception of race and the cultural context essential for the visual reading of race.

A common misconception among western audiences is one that mischaracterizes many Japanese anime characters as white because of their large eyes and non-black hair, while many in Japan consider them to be Japanese, or “mikokuseki” which means “stateless.” Simply put, the concept of mikokuseki means characters lack “othering” features. So a neutral character in Japan is assumed to be Japanese, just as a neutral character in America without othering features like almond-shaped eyes is assumed to be white. In her 2002 essay, “Seeing Faces, Making Races: Challenging Visual Tropes of Racial Difference” Kawashima makes this point, saying:

“Race itself can be defined as a visual reading process–that is, a process through which a viewer privileges certain parts and dismisses others in order to create a coherent whole according to assumed and naturalized cultural norms”

Impact

Why is all this important? It’s important to assess if and how images that users generate and share reflect the normative racial and gender displays in our broader culture because as we start using more visual generative AI tools, we have to be aware of the subtle and not-so-subtle gender display cues that we might be inadvertently incorporating in our media, reinforcing those that are already present.

More importantly, as the next generation of AI tools gets trained on data that includes AI output, we might find ourselves in a positive feedback loop for gender displays. In fact, these behavioral and postural cues will likely get more exaggerated as the push for realism ironically moves images to be more stylized, artificial, and mannerist.

Regarding this continued stylization and exaggeration, Goffman said this of advertisements:

“If anything, advertisers conventionalize our conventions, stylize what is already a stylization, make frivolous use of what is already something considerably cut off from contextual controls. Their hype is hyper-ritualization.”

His conjecture was that since gender displays were rituals in our everyday life, ads were “hyperritualizations”–an artificial layer on top of those rituals. So if advertisements are hyper-ritualizations, will AI media be “hyper-hyper-ritualizations”, even further divorced from reality, yet influencing how we see ourselves?

Russell Chun is an associate professor at the Lawrence Herbert School of Communication at Hofstra University. He teaches multimedia storytelling, design, and data journalism. He researches visual communication.

Comments

Post a Comment