"Translating Ourselves into Action" by María Reimóndez

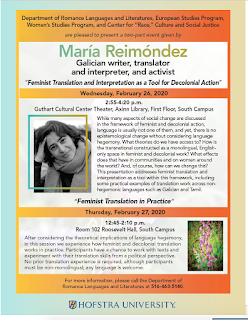

It is my last day in New York today and I start the day reading this article https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/blink/cover/we-see-you-faiz/article30999076.ece?fbclid=IwAR3MqJ1fPdfW_jRAwmogeKFHowoCj2RH9pbUzcjxj0nm5hM2twCM8WYtV1A about the translations of Pakistani poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s Hum dekhenge (We shall see) into Tamil, amongst other languages. The article explains how a plethora of women from different language communities across India have appropriated this Urdu poem to speak against the state and create strong alliances in times of disturbing political upheaval. “Carnatic vocalist TM Krishna, who performed the song in Tamil, Kannada, Malayalam and Hindi at Shaheen Bagh earlier this year, stresses that translations lead to “uncaging” of thought”. This sentence in particular made me smile, and the different quotations in the article took me back to my talk and workshop last week at Hofstra University, sponsored by the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, the European Studies Program, the Women’s Studies Program, and the Center for “Race,” Culture and Social Justice.

In my talk, I tried to take the audience through the history of colonisation past and present, seen through the lens of language hegemony, and argued how, unless we challenge the colonial idea that monolingualism is desirable, our work towards a fairer world will not materialise. I discussed how non-hegemonic language speakers are excluded from decision-making, and how we cannot survive without language diversity. The imposition of languages such as English or Spanish or Hindi on speakers of other tongues implies also a de-linking of communities from their own histories of resistance, be it in feminist thought and practice, the LGBTIQ+ community or the environmentalist movement. More often than not, it is only the hegemonic texts that we know, and this “epistemological funnel”, as I call it, contributes to the notion that some people are “backward” in their “nature” and others, the civilised, are advanced, and in a position to “teach/enlighten” others about their rights.

Discussing language diversity helps us undo these concepts and understand, for example, that in most colonised territories, from the Americas to Africa or Asia, there were varied visions of gender identity and sexual orientation that were almost erased during colonisation. The only reason we can still go back to them is because speakers have kept them alive in their own different languages. In all this, I also discussed how translation and interpreting were and are still used as colonial tools. How translation flows dictate that we, the Other, reads, watches, inhales English-language products at all times, thus perpetuating ideas of centre and periphery that create an unjust and unequal world.

Only when translation and interpreting are seen as tools for social justice and decolonial action, can we really go to the root cause of many of the power struggles we experience in the world at large today. My conclusion during the talk was what the article at the beginning of this post clearly shows: we need to talk to each other across non-hegemonic languages to create resistance to the power of the state, of the coloniser, of capitalism and interlocking patriarchies.

Sharing these ideas in front of an audience who was mostly non-monolingual was a joy. The questions that the students asked were filled with new understandings of place through language and, hopefully, a new beginning in reading their complex language identities. Many times, monolingual institutions forget that they are inhabited by people who are not monolingual and that their “other” languages are hardly ever acknowledged, let alone promoted. Very rarely do non-monolingual speakers get the chance to discuss their heritage in a way that is not objectifying. At university, rarely are students asked to look for examples of resistance in their own language communities.

One thing that was clear after the talk at Hofstra was that this topic affects monolingual subjects too. They might lack the language skills, but they usually have the power to create spaces for the non-hegemonic language speakers to find links to their own communities and share them with others.

As a continuation of this discussion I was very happy to conduct a small translation workshop during Professor Álvaro Enrigue‘s Spanish class. The idea was to help students experiment what being in the position of a non-hegemonic Other feels like, and have a first hands-on approach to the intricacies of the politics of translation.

While non-hegemonic language activists need to talk to one another, if we want power relationships to change, we also need to speak to those who are at the power centres. That rarely happens, but this time it did. The Hofstra community was ready to listen and I would like to particularly thank Professor Benita Sampedro for making my stay a wonderful experience. I depart with the hope of creating polyphonic worlds together and unite our voices to those of others, like the amazing women currently organising themselves around the translation of Hum dekhenge all over India show us. Outro mundo é possible / Another world is possible, if we translate our alliances into multilingual action.

María Reimóndez is writer, translator and interpreter, activist and feminist scholar from Galicia. Further details about her work can be found at her webpage: http://mariareimondez.com/index.php?lang=en

Comments

Post a Comment